Returning Community Ownership and Governance of Black Wall Street

Overview

Transformation in Tulsa

As part of Opportunity Accelerator (OA),a collaborative funded by Blue Meridian Partners to support equitable economic mobility, the Haywood Burns Institute (BI) provided technical assistance to the City of Tulsa and PartnerTulsa (Tulsa Economic Development Authority) to design a community-owned governance model and associated development entity to implement, lead, and manage the transfer of 56 acres in the Kirkpatrick Heights-Greenwood districts.

The History

Greenwood, Black Wall Street

- Black households live on 40% less than white households [1]

- Eviction rates are 1.6 times higher in majority non-white census tracts than in majority white tracts [2]

- Black unemployment is twice that of whites [3]

- Black poverty is three times higher than whites [4]

- Black bachelor degree attainment is half that of whites [5]

- White residents are twice as likely than Black residents to own a home [6]

To help redress these cascading injustices after hearing from Tulsa’s Black community, in 2021, Tulsa mayor G.T. Bynum committed to transferring 56 acres of land within Greenwood to community ownership. With the help of consulting partners, the Greenwood community, and PartnerTulsa, the City embarked upon the design of a community-owned governance model and associated development entity to implement and manage a development plan for Greenwood.

STAFF REFLECTION

Black Population Data

By Clarence Ford

BI's Role

Transformation in Tulsa

With the goal of driving equitable, long-term economic mobility, and restoring the legacy of Black Wall Street, BI guided City representatives and the Greenwood community through BI’s Structural Well-Being Framework which centers communities and anchors stakeholder groups in history, values, working agreements, and shared humanity.

STAFF REFLECTION

Arriving In Place at Tulsa

By Sandra Sosa

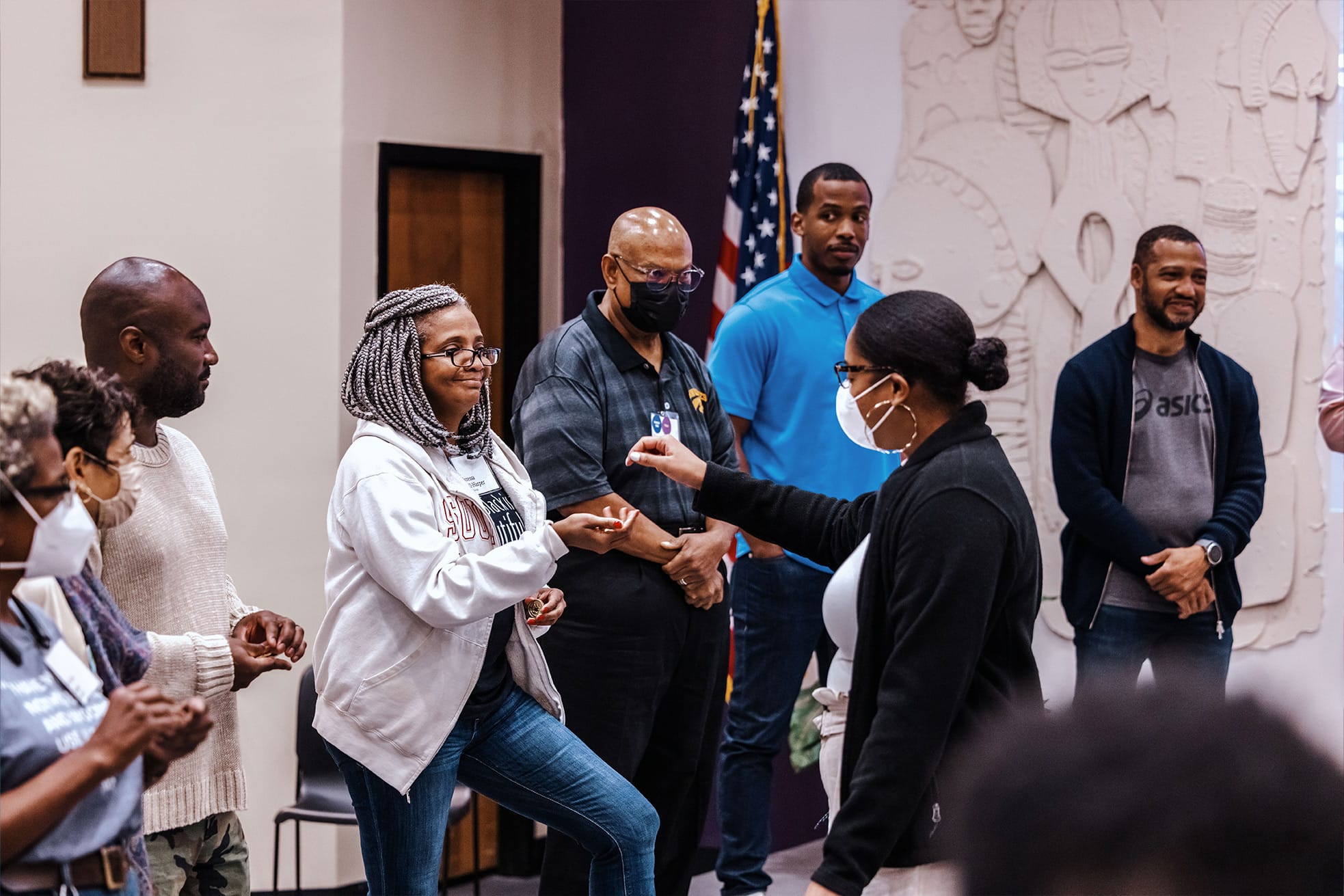

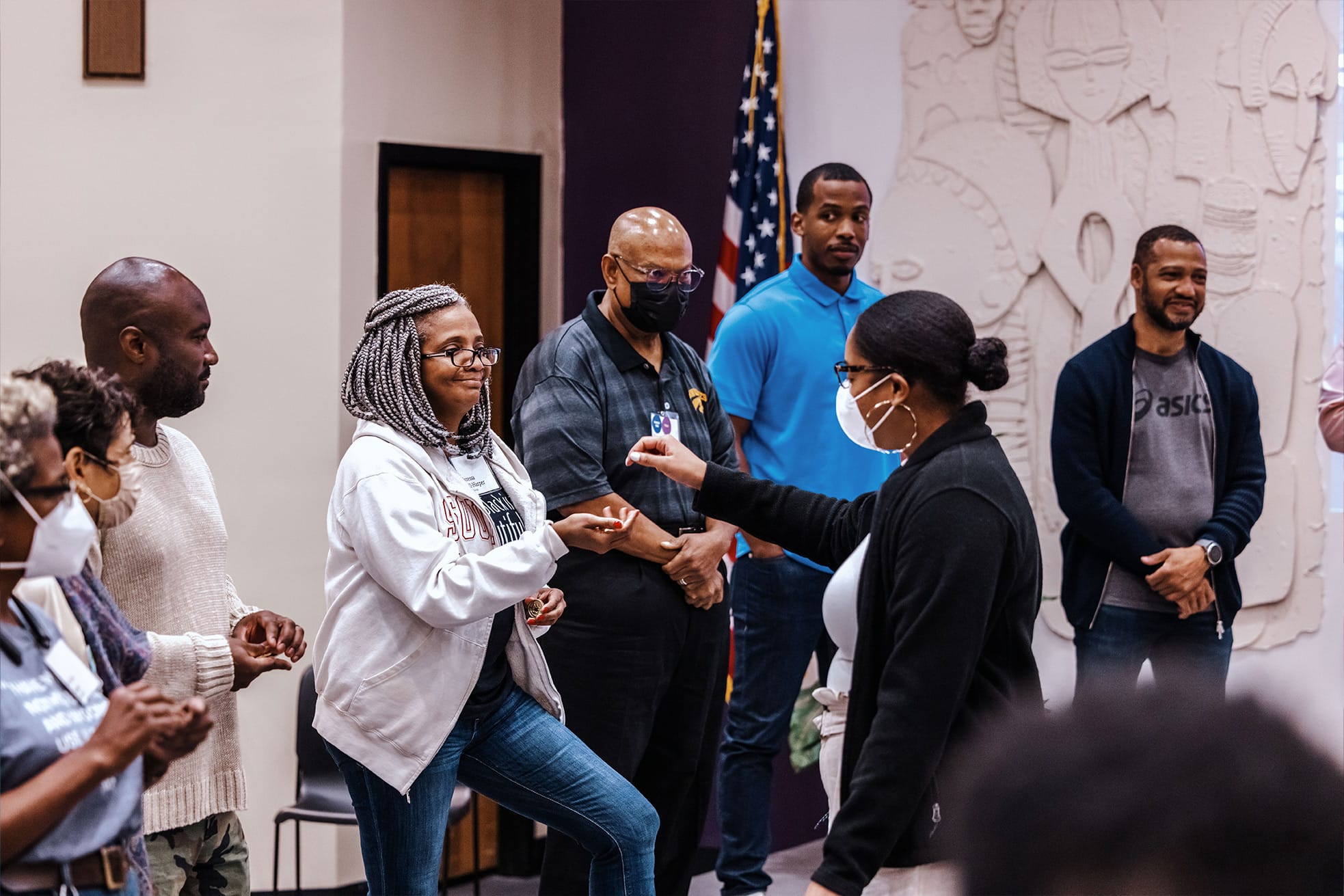

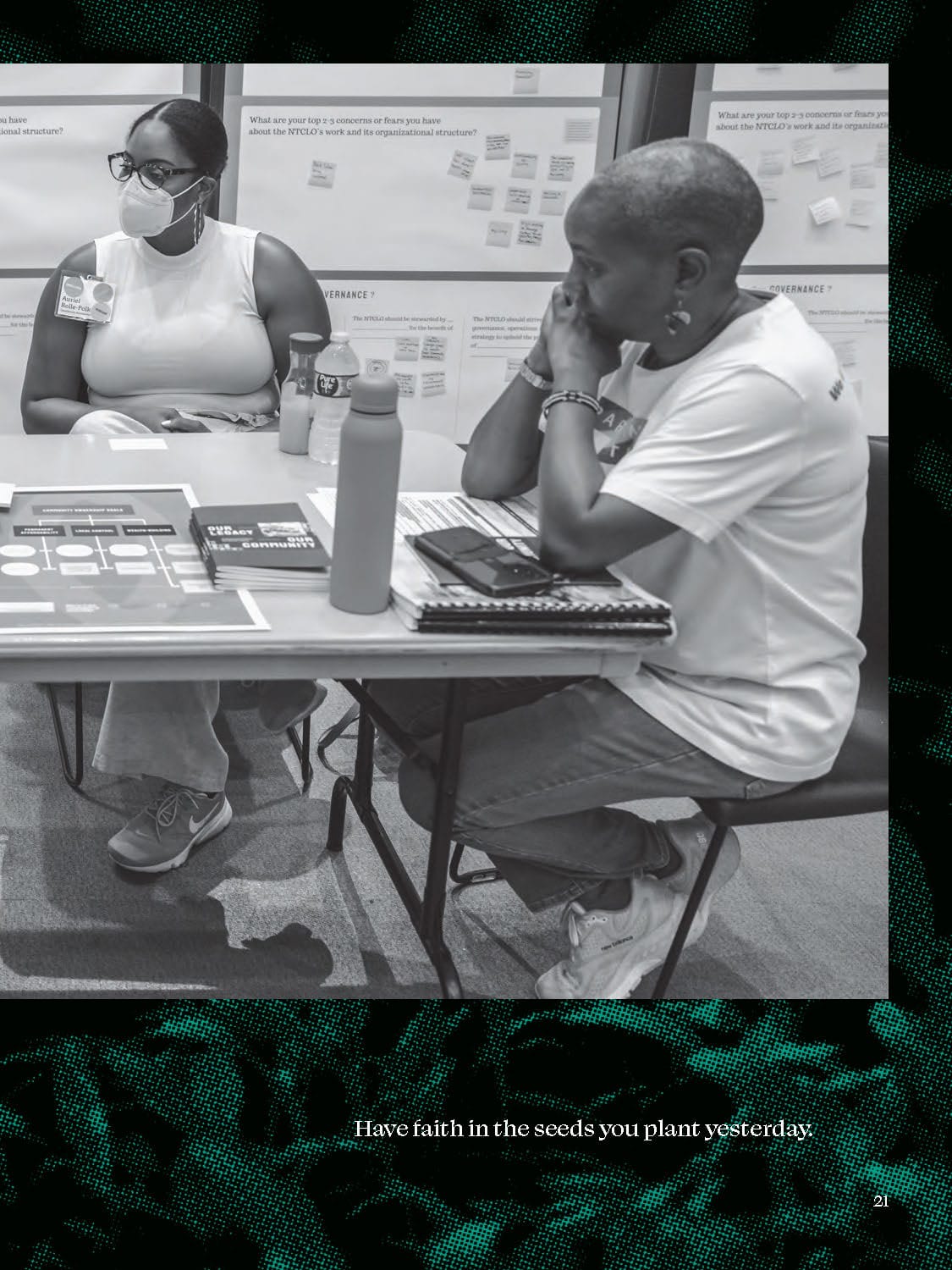

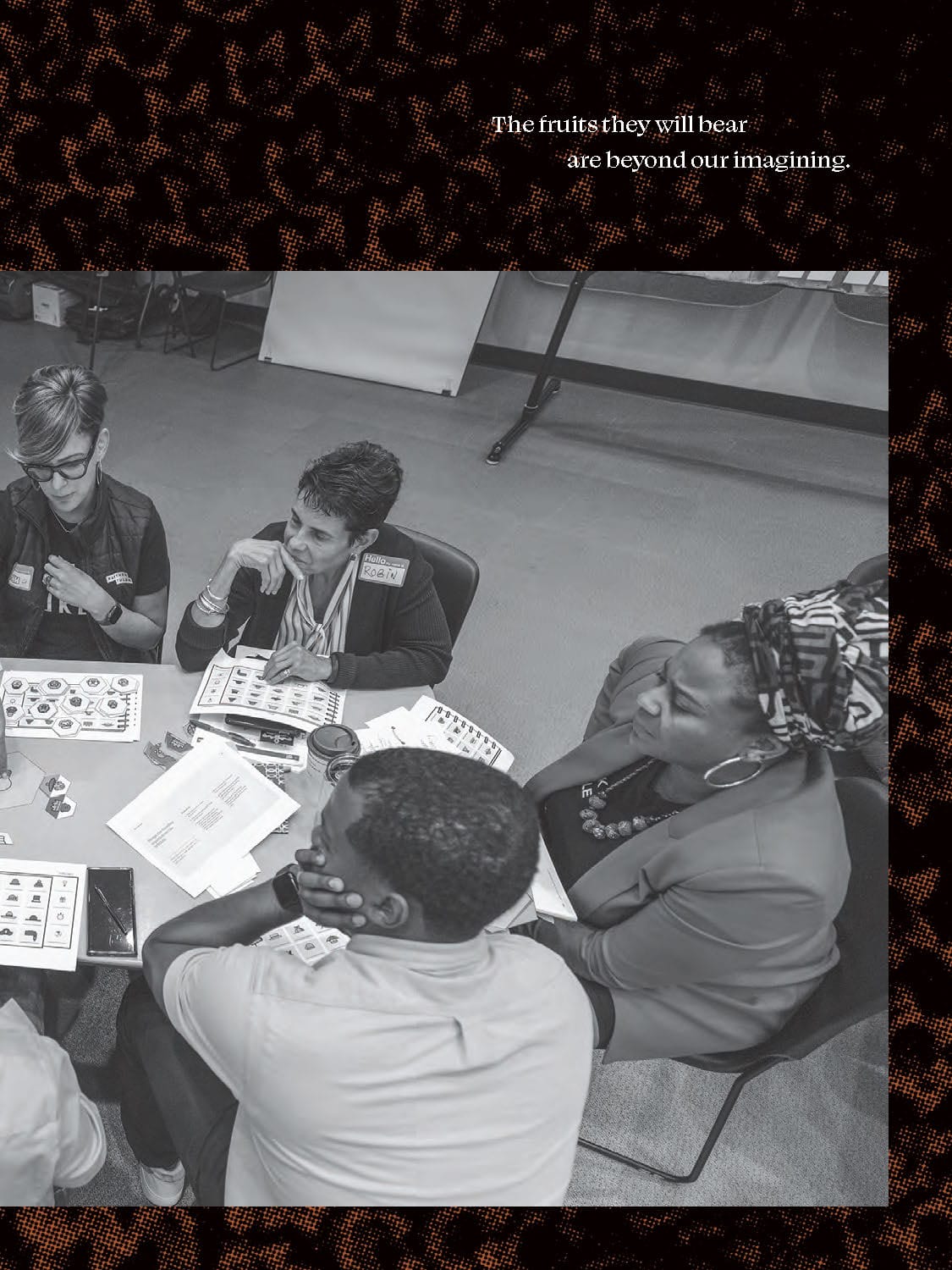

Tulsa Community Governance Workgroup

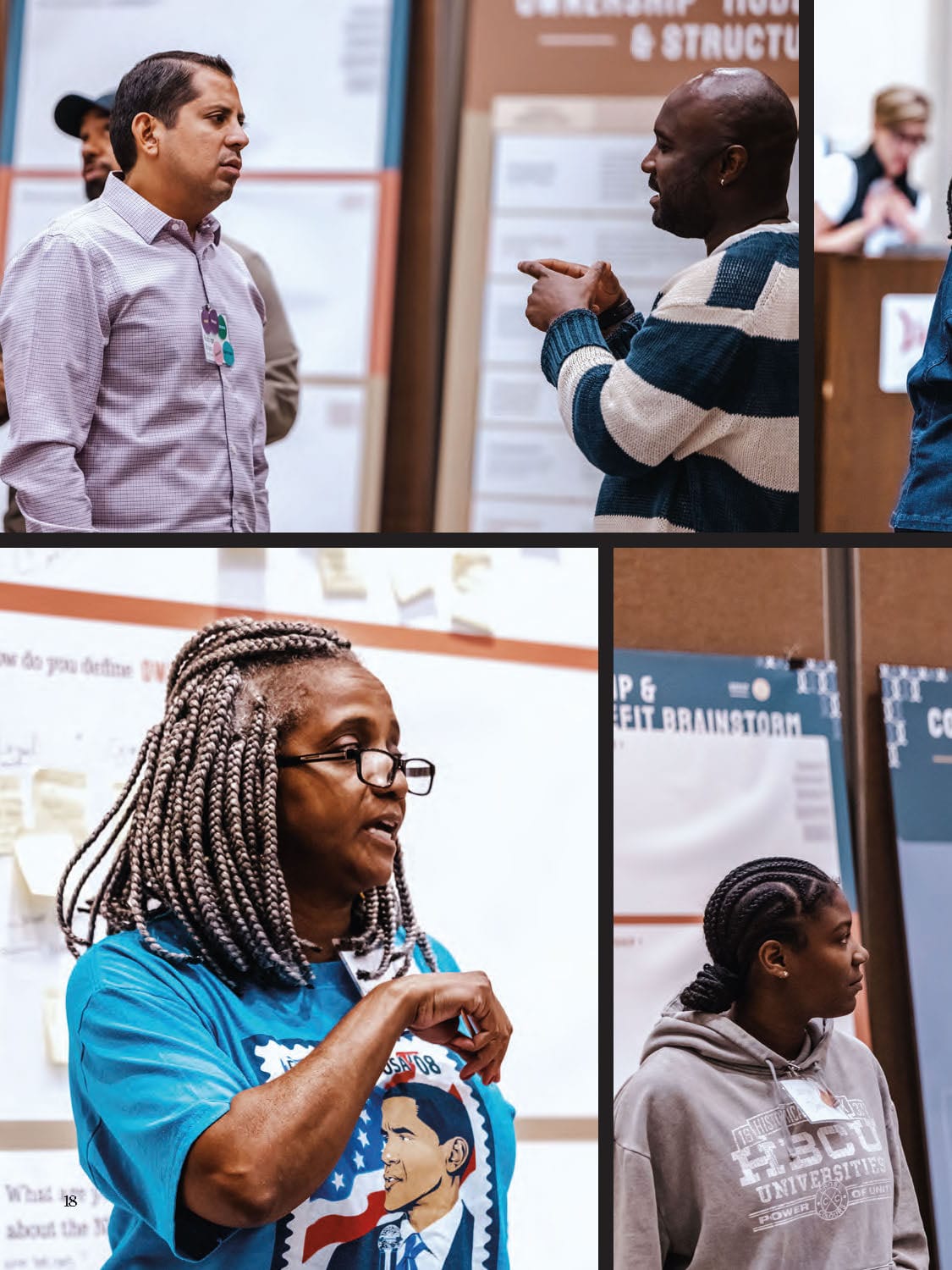

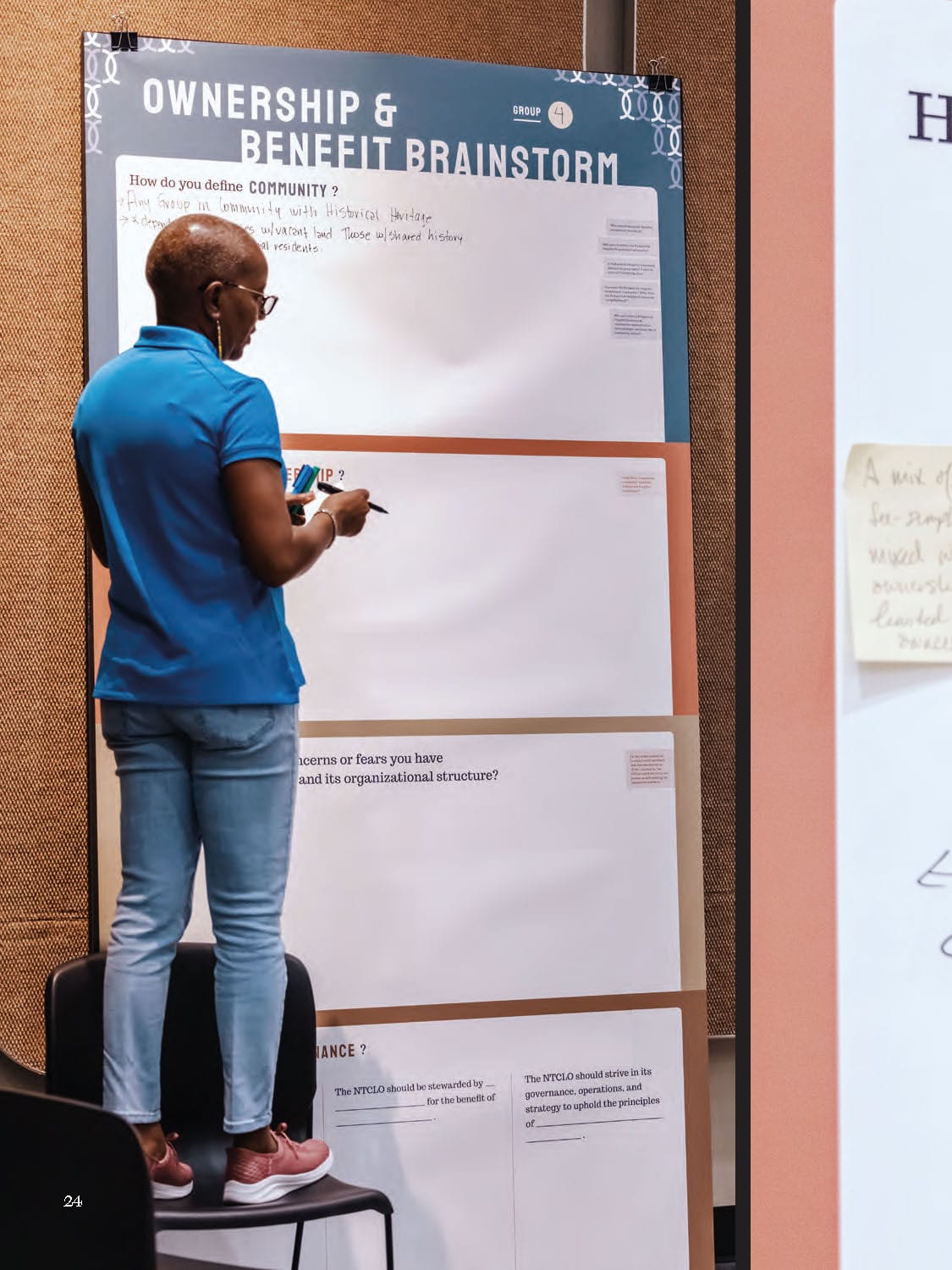

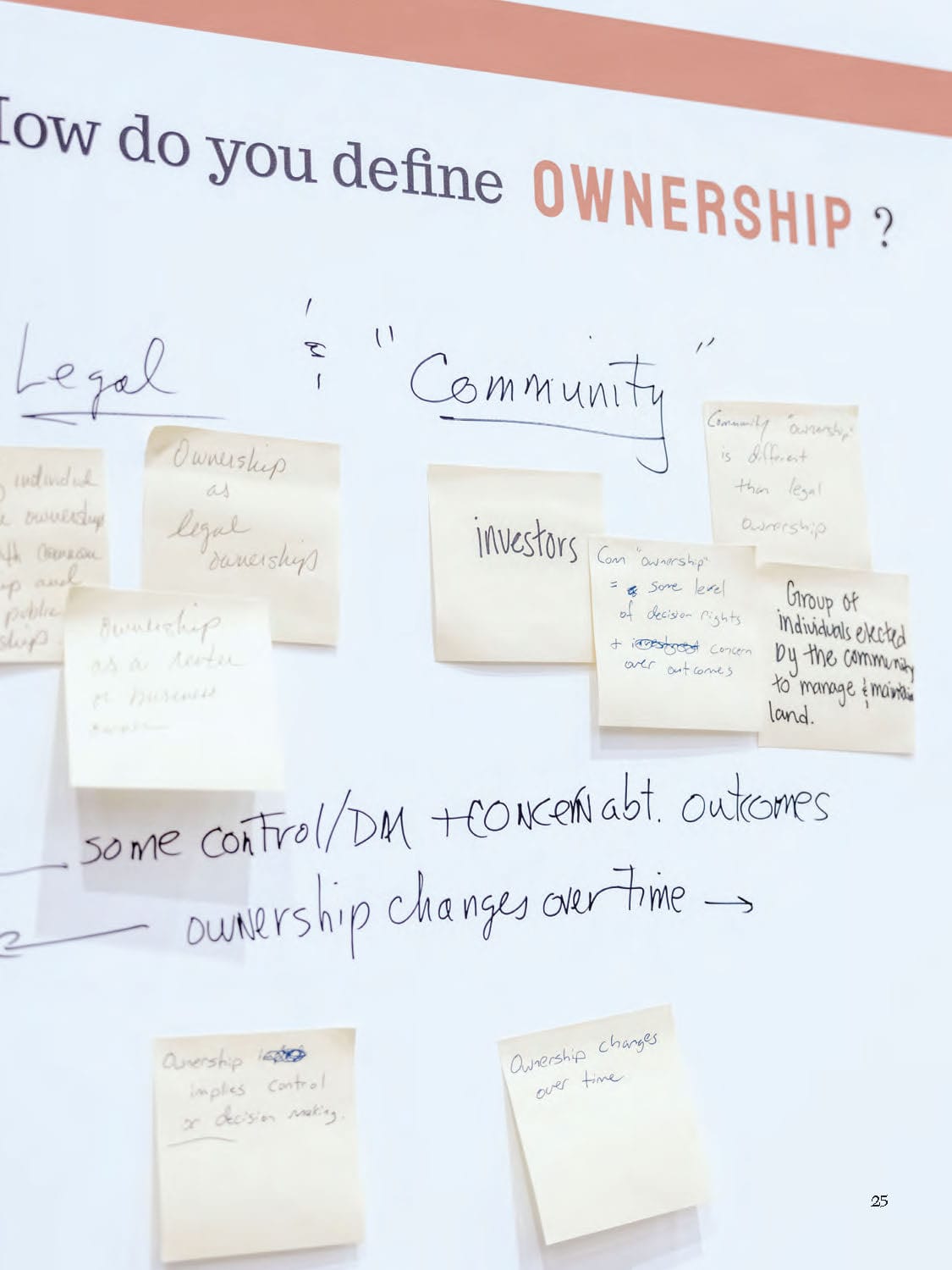

Greenwood stakeholders deliberated on what is meant by wealth, who will benefit from the development, what ownership looks like, and what signifies success. The community defined wealth and economic mobility not only monetarily, but as a preservation of Black history, generational legacy, culture, and health:

The definition of ‘Black wealth’ goes beyond just money and assets—it means equality, opportunity, independence, legacy, and passing down knowledge and resources to future generations.

Honoring community culture and representation, the workgroup designed a governance structure that is highly participatory and chose a Community Development Corporation (CDC) as the overarching legal structure to lead and manage development of the 56 acres.

The work of the Kirkpatrick Heights Greenwood master planning effort is inspiring, exciting, and hopeful. We have an unprecedented community centered design process that includes voices from young to elderly residents, business owners, creatives, students, community leaders and advocates, and more.

“Because of this intentional, transparent process, we have a clear roadmap for development along with options for sustainable community ownership and oversight. This process and future implementation serve as a blueprint for subsequent co-development of master plans in our city and across the country.”

Ashley Harris Philippsen Leadership Committee Co-Chair

"Because of this intentional, transparent process, we have a clear roadmap for development along with options for sustainable community ownership and oversight. This process and future implementation serve as a blueprint for subsequent co-development of master plans in our city and across the country."

Ashley Harris Philippsen

Leadership Committee Co-Chair

Four Approaches

BI has chosen four key approaches from this immense community-city undertaking that we believe account for the partnership’s success, and we offer them for others to utilize in their processes toward transformation.

Acknowledging harm, anchoring shared values, practicing belonging, and co-creating can bridge tragic histories to ensure effective partnership that keeps everyone at the table.

Despite its long, punishing history, Tulsa’s Black community continues to advocate for justice and reparations. As in any community, however, there are varying conceptions of repair and justice. There is also warranted distrust of the City given the long history of oppression and still-present trauma. Notably, building and strengthening community trust was not included in the City’s proposal but emerged as a critical priority.

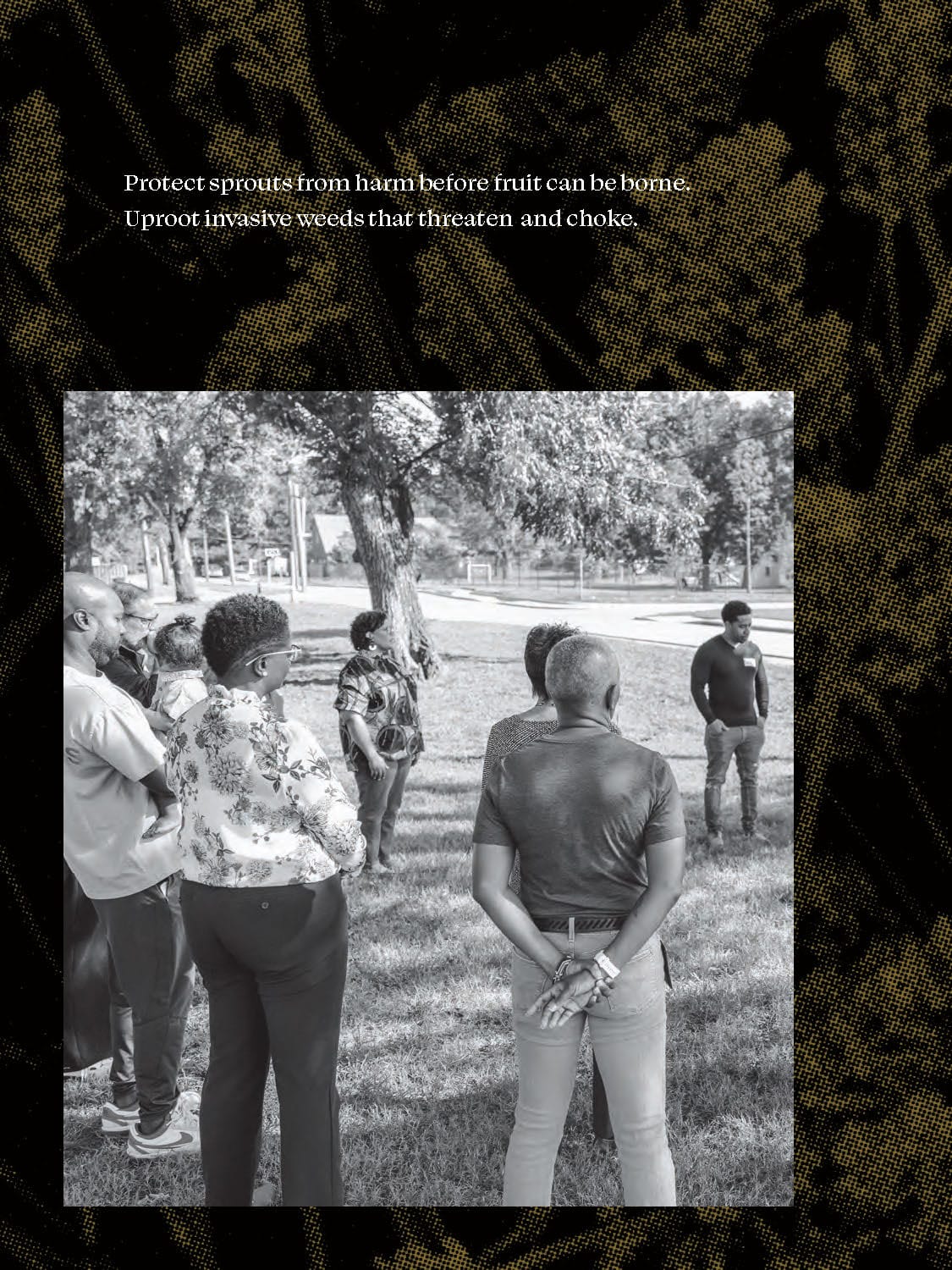

Therefore, as BI entered to support the community in designing the governance and development structure that would implement the Kirkpatrick Heights-Greenwood Master Plan, we prioritized supporting stakeholders in coming together across differing points of view and low levels of trust. This, we knew, was a core part of effectively co-designing the future.

Given the community’s distrust and anger as we were to launch the first in-person workshop (June 2023), we led the workgroup in a circle process to examine recent wounds that an associated development project had opened. It facilitated open, honest dialogue and enabled the workgroup to name the systemic patterns that needed to be interrupted and dismantled for forward movement and partnership between government and community to be successful. This restorative justice and bridging work enabled effective partnership and deliberation, which allowed this community to co-design a community-owned governance structure to implement the vision for well-being and resurgence of Black Wall Street.

BI’s Structural Well-Being Framework and Place-Based Approach guided the overall design of consultants’ engagement with Tulsa. Core to BI’s approach is centering communities typically marginalized, and anchoring stakeholder groups in history, values, working agreements, and shared humanity.

Here are two key principles of BI’s process:

- Intentionally create the conditions for belonging. This is about creating a space that ensures everyone present can enter, contribute, and feels welcomed and honored. Ensuring each person feels equally invited to contribute their dreams and ideas is critical to innovation.

- Co-creating is core to belonging. When we co-create, we do not have an end state in mind. We are open to finding what is possible together. Each engagement was intentionally designed to ensure shared ownership to allow for co-creation.

Community-level solutions require whole-community partnership. Dismantling structural racism and structuring environments for well-being impacts the entire ecosystem. This level of transformative work needs trust and effective deliberation, especially in disagreement. Building to achieve a fundamental shift in outcomes for communities of color requires a new set of values to anchor design. It also requires acknowledging harm, humility, and courage to move toward repair.

Building trust, bridging differences, and anchoring in values are core to addressing past harms and building effective partnerships.

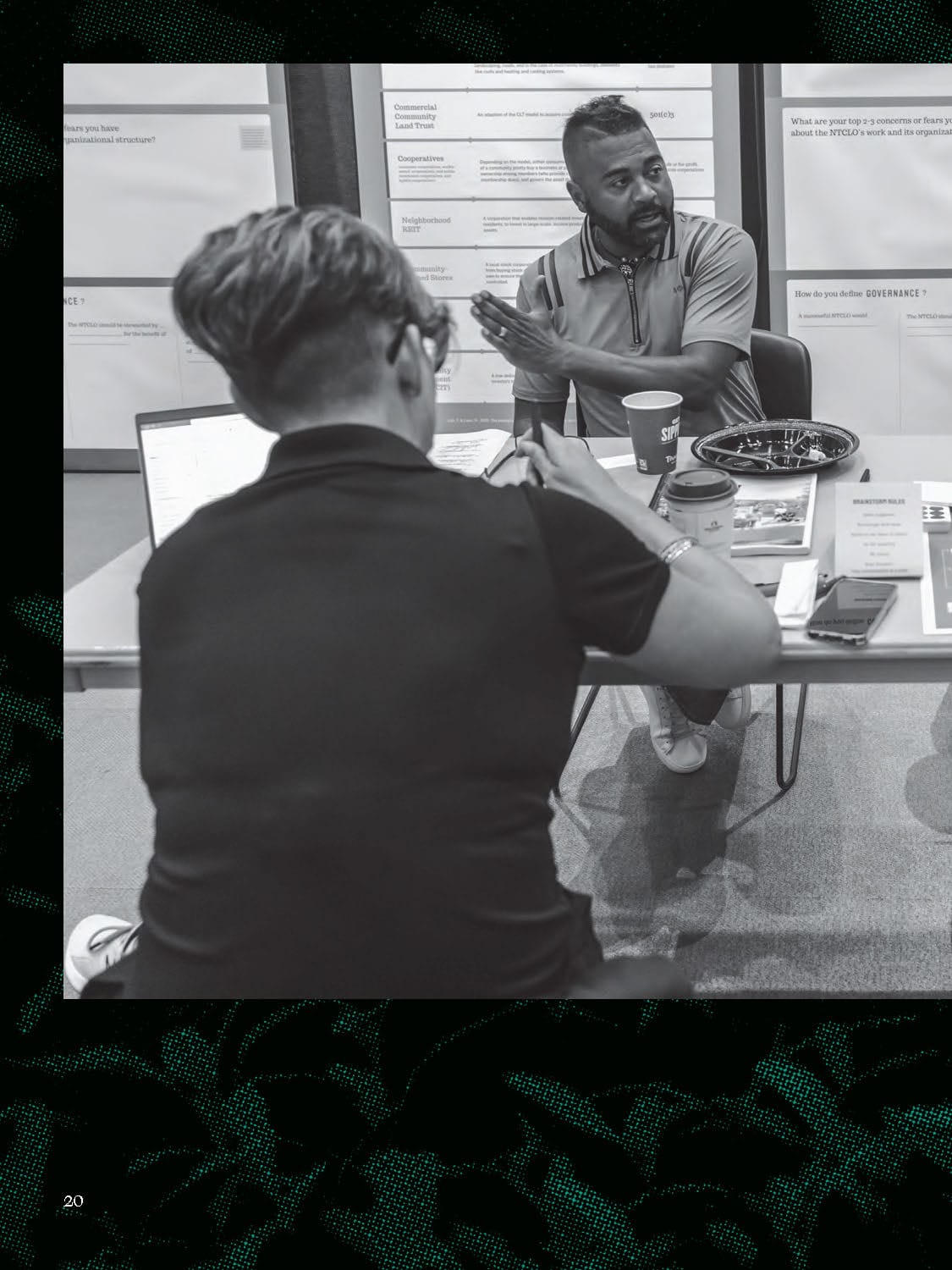

At the outset of the process, the workgroup developed group norms, working agreements, and values to anchor design and deliberation, with two key provisions guiding the creation of their recommendations:

- Strive for consensus. Expect and accept non-closure, embrace discomfort. Building consensus will take time, and we may not always be able to “tie a neat bow.”

- Incorporate the views/concerns/values of minority perspectives.

Applying these norms, agreements, and values was challenging. While the majority agreed to begin with a Community Development Corporation incubated by PartnerTulsa, it became difficult for the workgroup to practice its values while debating a dissenting minority viewpoint which seemed to jeopardize months of work. To the contrary, however, including the “safe to try” conditions of the few dissenting voices made for a stronger set of recommendations for securing commitment to release the land to community ownership within a set timeframe and clear conditions around PartnerTulsa’s role to shepherd the governance model “from incubation to independence”—a core justice goal in the vision for Greenwood.

The workgroup offered the following recommendations:

- Establish a Community Development Corporation (CDC) as the overarching legal structure to lead and manage development of the 56 acres.

- As specified in the Master Plan, PartnerTulsa will help incubate the CDC from creation to independence according to conditions and timeframe incorporated in a legally binding vehicle such as an MOU as further specified by the Advisory Committee.

The City and PartnerTulsa have taken an unprecedented opportunity to model the possibilities of meaningful community collaboration to redress the gross injustice and resulting inequalities arising from the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Yet, returning the affected areas to a condition of well-being, equitable development, and vibrancy benefiting all residents, particularly Black North Tulsans, requires a commitment to eliminating systemic barriers that limit or prevent access to quality jobs, housing, and wealth attainment. It also requires intentionally accounting for and including the shared experiences, history, challenges, and needs of the people, and because of this commitment to focus on building bridges of opportunity together, centering impacted people in decision-making. Mayor Bynum selected an 11-person leadership committee, representing a cross-section of North Tulsa leaders, to work alongside City staff and PartnerTulsa to ensure a community-centered process.

The Kirkpatrick Heights Greenwood Area Master Plan is one of the most significant real estate projects in the City’s history and execution of the plan will create a range of retail, cultural spaces, amenities, and provide a variety of housing. Mayor Bynum’s message to North Tulsa community leaders from the beginning was simple: the City and TDA own the land, but whatever happens must reflect the aspirations North Tulsans have for the site—so whatever North Tulsans decide is what the City would do.

PartnerTulsa was created by an assembly of traditional economic development boards and authorities—one of which executed the urban renewal plans that decimated the community fabric and reshaped this entire community. While having that entity work with the community to co-design its future was transformative for Tulsa, it also meant that processes had to be more deliberate, intentional, and collaborative. And moving at the speed of trust meant processes could be slower, take longer, and could often be triggering for participants. This process, therefore, required that we sometimes adjusted expectations and gave space for grief to promote healing. Governments and private-sector business entities do not traditionally do this, but this community-building process was vital. Ensuring qualitative feedback and outcomes are emphasized in how we measure success is extremely important.

Power-sharing is difficult, particularly in real estate development projects, where only a few individuals make the decisions. The community identified that they defined growth, progress, wealth, and ownership more broadly than conventional processes often account for. This challenged practitioners implementing the Master Plan, as they also had to consider the fiduciary interests of the authority transferring the property.

Though the importance of the process sometimes eluded participants, the approval of the Master Plan by both the Tulsa Planning Commission and the Tulsa City Council is a testament to its efficacy. This includes garnering the support of community members in presenting and having the Master Plan and the resolution adopted by the Tulsa Development Authority to support the formation of an Advisory Committee to create a Community Development Corporation. These deliberations occurred without public protest and through unanimous votes from various bodies. The City of Tulsa, PartnerTulsa, and the many entities it represents are learning valuable lessons for this type of deep and sustained community engagement.

New, just, and innovative strategies require intentional, creative co-design.

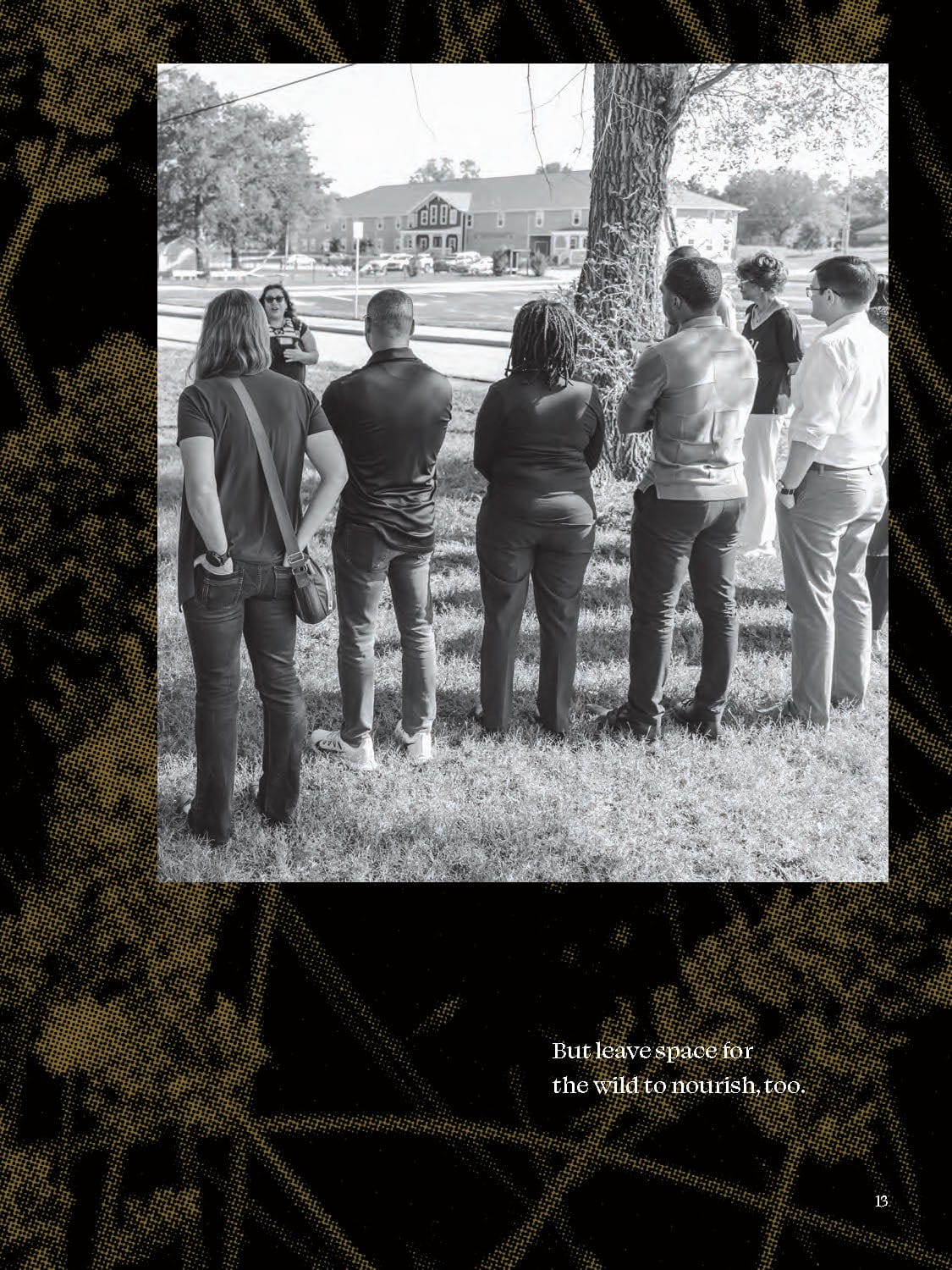

Radical Futures, led by Founder Tracee Worley, brought inspiration to the workgroup process through imaginative, fun, and creative activities, such as field trips showcasing four communities implementing community owned-real estate efforts, and conversations with innovative scholars and practitioners. Aspects of human-centered design and futures design, including speculative futures, provoked thinking and provided visceral connections to potential change.

Imagining alternative structures that support well-being requires intentional facilitation strategies incorporating diverse, intergenerational perspectives to break through restrictive, status-quo thinking. Speculative futures shift the mindset from “What’s the problem?” to “What’s possible?”

STAFF REFLECTION

When I Think of Tulsa

By Christopher James

- Communities need healing—to move beyond the pain and mistrust and to co-create a new vision alongside the very same systems that have harmed them. Healing is a process and cannot be rushed.

- Systems may want to see themselves as the heroes of stories about community ownership, but they are not. They must support, partner, and amplify community development with the skills and resources they have.

- Community members have often been so busy fighting power that they’ve lacked space and time to consider how to wield power and make decisions about the changes they want to see.

- Community trust is vital. While community members should never be expected to trust blindly, system transformation is impossible without their trust and genuine, active participation.

I’m proud to be a part of this work, proud of the community who, despite their skepticism, chose to believe in the future they want for generations to come and have chosen to move forward in the way that best suits residents of North Tulsa. I look forward to seeing the ultimate collective vision brought to fruition in the not-so-distant future!

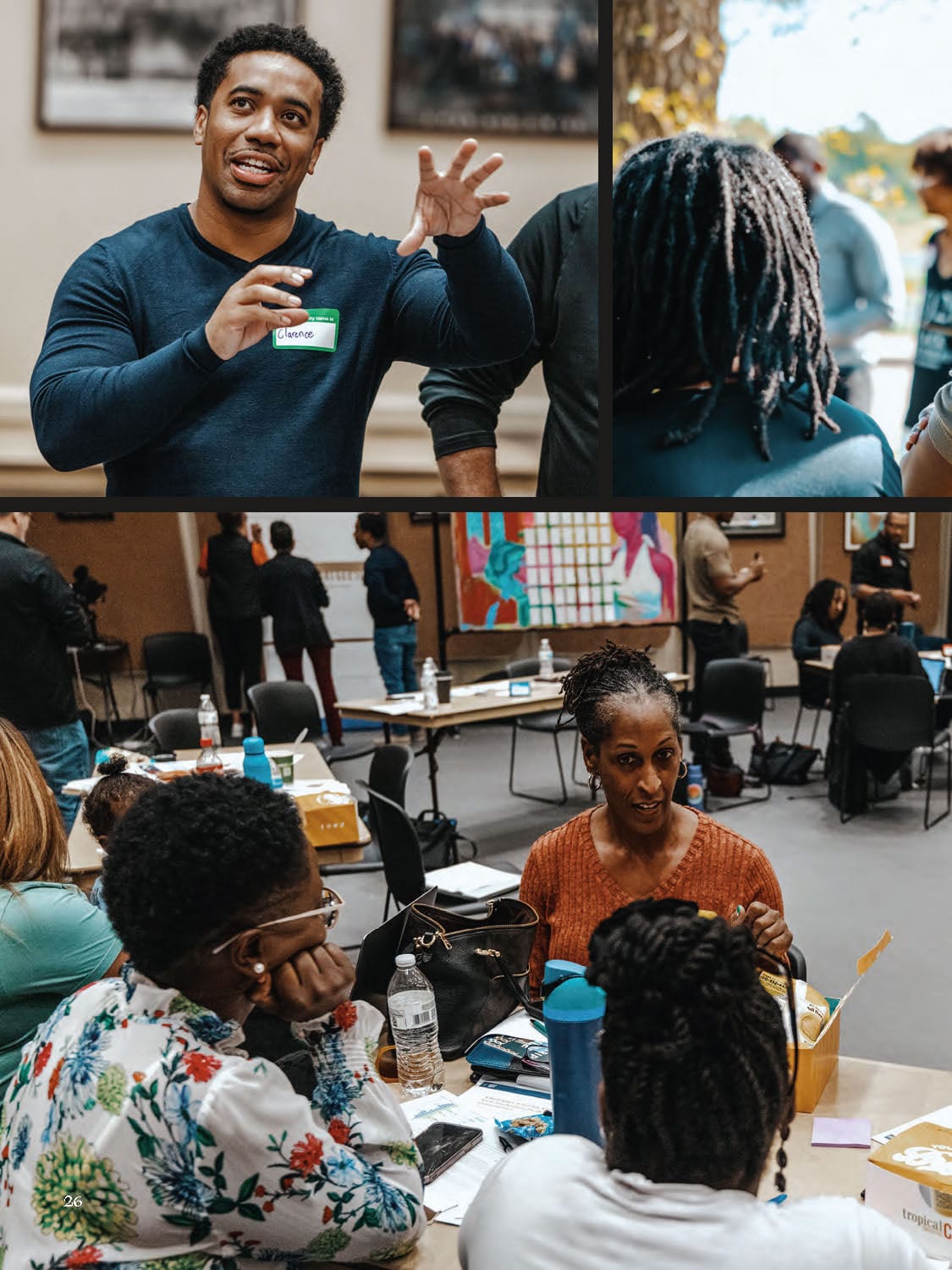

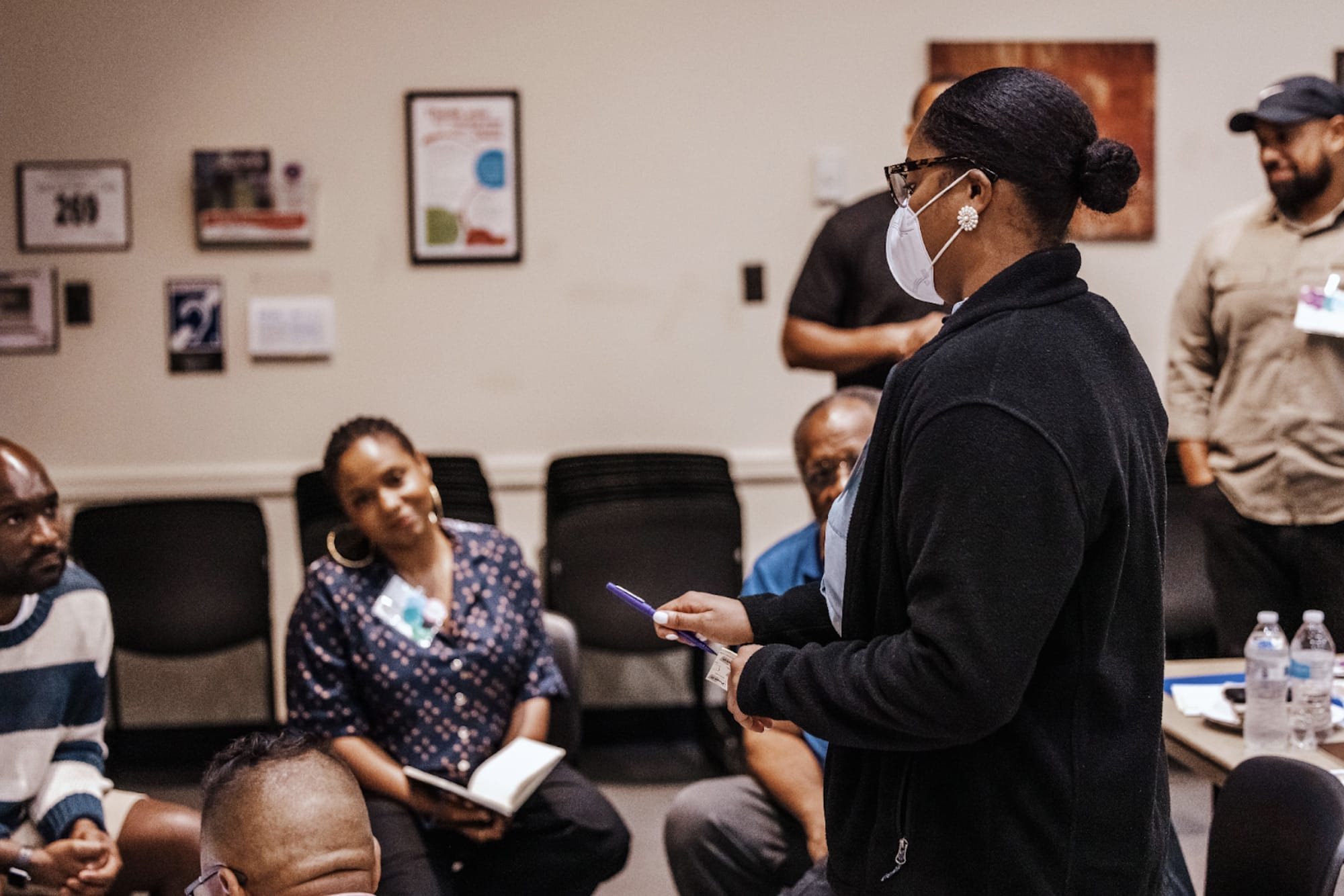

Photobook

Acknowledgements

This work reflects collective effort from incredible partners and, most importantly, the Tulsa Greenwood community.

Tracee Worley and Alysha English

Radical Futures

Ben McAdams and Shayne Kavanaugh

Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA)

Sam Christensen

Results for America (RFA)

Andrea Calderon, Latricia Boone, Laurie Moise Sears

Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center for Government Excellence (GovEx)

Auriel Rolle-Polk and Clara Asumadu

Code for America (CFA)

Jordan Sanchez

BI consultant

Robin Delany-Shabazz

BI consultant